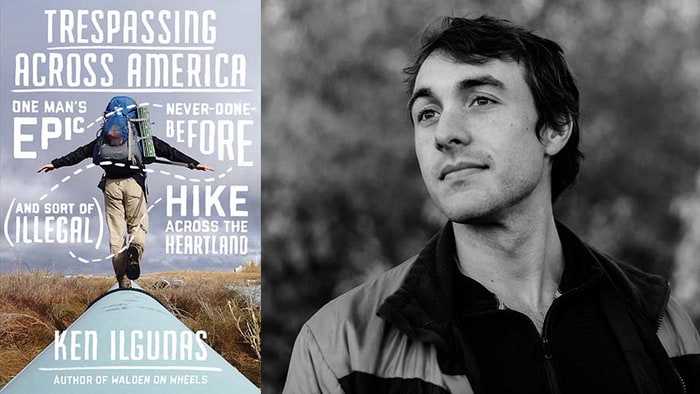

We all take walks, but Ken Ilgunas had a weird idea to go on an especially long walk. Why was it weird? He wanted to walk the length of the proposed Keystone Pipeline, from the wilds of Canada through the Great Plains and to the Gulf Coast of Texas. Walking and sprinting, hitchhiking, and finding any way possible to see all 1,500 miles to not only draw attention to global warming and our dependence on oil, but also see how far he could push himself. What he ended up writing, Trespassing Across America, a combination of Thoreau, John Steinbeck, and Ian Frazier, is an unforgettable read. We’re proud to present this except from it.

Is there anything more rhythmic than the motion of walking? There is an undeniable elegance in its swinging limbs, its clockwork symmetry, its mechanical momentum, its choreography of balance. The human stride is one of our biological blessings—a dazzlingly complicated operation that requires little conscious thought. It frees our minds to plan and dream and think as our body lurches forward, handling the business of breaths, pulses, pores, and the million rotating gears necessary for just one successful step of an amble. Your shoulders and hips rotate. Your arms gently wag, greased by pints of sweat flooding from your armpits. Your back is straight. Your head is level, looking ahead, lightly bobbing with each footfall. Your knee bends, and your leg straightens, bends and straightens, bends and straightens. Your body falls forward but is saved by the next placement of your foot that meets the ground in front of you at just the right second. The ball of your heel is planted, the arch of your foot rolls with the shape of the terrain, and your toes launch you forward into the majesty of bipedal locomotion: an evolutionary triumph that has freed our hands to build and throw and gather, granting us the means to leave our past in the confines of the jungle and set our sights on the unconquered glories of the open savannah.

There may be nothing more human than the act of putting one foot in front of the other. It’s a potentially unwieldy method of transportation when you think about it. Most other animals have another two legs on the ground (or, in the case of primates, long arms) to keep them balanced and upright. We are the awkward unicyclists of the animal kingdom. (Remember that we spend most of the time walking with only one limb securing us to the ground.) Each step forward is like a leap of faith—an act of hope that we won’t topple and will land okay so long as we take another step and another step after that. And perhaps there’s no better symbol for the boldness of the great human experiment than the walk, as each springy step contains the same extravagance, cocksureness, and audacity present in the greatness of our pyramids and the arrogance of our tar-sand pits.

You’re in that late-morning, mid-afternoon sweet spot when the soreness of yesterday has dissipated and the soreness of today has yet to surface. You begin to feel a dull and pleasant heaviness overtake your leg and butt muscles. You feel your thighs turning into rock-hard muscle, your stomach flattening, your calves turning into two speed bags of death. The calories boil away, and you feel as if you were the most in-shape person on Earth: a healthy, hot, hiking sex god. Time slows down. Days get longer. You feel as if you’ve walked an hour, and you look down at your watch to see that only ten minutes have passed.

Going on a long walk across the country is such a change of life- style that it’s about as close as you can get to experiencing life as a different person. A journey is so full of unfamiliar circumstances that you have no choice but to deal with life’s trials in unfamiliar ways. To deal with the mental, physical, and emotional rigors of a journey—when every day, every step, every person is different from the previous one—you have to take on a multitude of new roles because your old ordinary self is just not equipped to handle this cascade of newness.

Normally, in North Carolina, I played the role of a gardening, writing, van-dwelling recluse. In Alaska, I was the solitary, nature-loving book nut. Back at my parents’ home in New York, I was a beer-drinking, video game playing bedroom hermit. Each place brought out a slightly different side of me, but wherever I went, I was essentially the same crowd-shy introvert who favored being by himself. It was as if gravity—or some indomitable force—would pull me back to that persona no matter where I lived, despite the fact that I didn’t always want to return to that rather limited person. Yet I’d feel a dull comfort in my own company and in my routine of eating, jogging, reading, writing, working, and movie watching. The routine of my life followed me everywhere.

But when you travel—especially when you travel alone—you have to adapt to a whole new routine because that old solitary, sedentary person you were just won’t cut it. You have to change. You have to broaden. You have to become not just another type of person but many different types of people. Of course, part of me would remain my normal introverted self, but I’d also have to become sociable, extroverted, charming, cunning, crafty, bullshitting, bold, confident, and careful.

If you’ve ever traveled for a period of time with a group, you’ve probably noticed that the individuals within the group will almost instantly specialize and adopt well-defined roles. I once went on a two-month-long canoe voyage with two other guys, and within days, without anyone verbally assigning roles, we automatically adopted routines and roles. One guy became the leader, navigator, and canoe repairer. Another became the emissary who did all of our talking for us. I became the expedition’s baker, pot washer, and mule. It was an efficient setup, and we were more effective as a team this way, and our daily tasks suited each of our ordinary personalities. But I regret that for those whole two months I never once looked at a map. I never learned to navigate, repair a canoe, or suavely persuade a property owner to let us camp on his land.

When you travel alone, you have no choice but to play all of the roles. You have to be the whole team. You have to be all seven samurai. On my hike, I was the navigator, cook, mule, diplomat, tent erector, water purifier, blogger, book reader, psychologist, emotional picker-upper, singer, conversant, dog whisperer, bodyguard, nutritionist, hemmer of tears, cleaner of self, camp organizer, logistics coordinator, medic, and wannabe environmental crusader.

And in so doing, I felt like a richer, more self-reliant person. All of my senses had become keener. I was constantly looking to horizons, seeking good paths. When stealth was required, I listened carefully for cows or trucks. Going over a hill, for the first time in my life, I smelled an animal (a faintly pleasant oily wildness) before I heard or saw it: a coyote, half-amazed, half-terrified, tripping over itself as it sprinted away, too bewildered to take its eyes off of me. My mind and body, awakened from their torpor, felt invigorated, healthy, alive.

Source: Men’s Journal

June 2016

http://www.mensjournal.com/entertainment/articles/walking-as-meditation-an-excerpt-from-trespassing-across-america-w205944