Simone de Beauvoir started hiking in 1931, when she was in her early 20s and assigned to Marseille to teach secondary school. She wrote in her memoir “The Prime of Life” that she at first viewed her post with dread. It was 482 miles from Paris, from her friends and from Jean-Paul Sartre, her lover. But she was surprised that she liked the city, “the smell of tar and dead sea urchins down at the Old Port” and “the clattering trams, with their grapelike clusters of passengers hanging on outside.” And then she found an obsession, hiking, “transforming my exile into a holiday.”

For the duration of the school year, she made it a rule to be out of the house by dawn on her days off, “winter and summer alike.” She would map walks that would last five or six hours, then nine or 10, traveling on some days as much as 25 miles. She was gripped by a “mad enthusiasm.” She climbed every peak in the region, “explored every valley, gorge and defile” and would organize vacations around her walking expeditions for the next 20 years.

Beauvoir is remembered as a philosopher, feminist and novelist, not as an outdoorswoman, and yet pages of her memoirs are taken up with descriptions of the hikes she took in her 20s and 30s: in the Maritime Alps, the Haute-Loire, in Brittany, in the Jura, in Auvergne, in the Midi. Since the publication of Cheryl Strayed’s “Wild” or even Robyn Davidson’s “Tracks,” it has become commonplace to see the solo excursion in the wilderness as a possible experience of feminine catharsis. Beauvoir abhorred sentimentalism in her writing and seemed constitutionally incapable of contriving a sudden epiphany after cresting a peak, but it turns out that in addition to all of her philosophical contributions she is a forgotten pioneer of this genre of memoir. She would describe the passion she developed that year, and the completist drive she brought to it, as emblematic of her “particular brand of optimism,” where “instead of adapting my schemes to reality I pursued them in the teeth of circumstances, regarding hard facts as something merely peripheral.” Beauvoir did her hiking in a very particular way. It was a popular pastime in Marseille, where there were many alpine clubs, and her colleagues would often take day trips in groups. Beauvoir hiked alone. She rejected “the semiofficial rig of rucksack, studded shoes, rough skirt and windbreaker,” instead traveling in an old dress and espadrilles. For food, she brought a picnic basket with some bananas and buns in it. She took buses to her starting points and hitchhiked between trails. She saw her colleagues’ warnings that she would get raped as “a spinsterish obsession,” and wrote, “I had no intention of making my life a bore with precautions of this sort.”

I read “The Prime of Life” for the first time in 2013, coming across a water-stained mass-market paperback from the 1970s in a house in Cape Cod, a copy that I stole upon departure. I justified the theft because the book was old and crumbling and because some minute insects, the kind that smear when you brush them with your finger, had taken up residence in its damp pages. It was not a great time for me, the summer when I read her memoir. I marveled at Beauvoir’s obstinacy, her commitment to happiness and the willful ideology by which she shaped her existence. In the era in which she had chosen to reject monogamy, cohabitation and children, her declarations represented an anomaly. Now many women have this kind of life, whether by accident or intention. I had been thinking of my own situation as an accident, a more or less unpleasant one, but Beauvoir provided an entire philosophical justification for why it might represent a better way to live. And here, in her excursions, was a way to find enjoyment in solitude.

This past June, I took a bus and then a taxi from Nice as far as I could ascend into the Maritime Alps. I had hoped to vaguely recreate a trip Beauvoir had made in Provence in 1939, what she called “the most delightful of all my walking tours.” I had planned to hike north from a hamlet called Bousiéyas in the direction of a town called Larche, near the Italian border, which in 1939 Beauvoir had found so occupied with troops she couldn’t get a room, but the mountain pass to Larche was still covered in snow. I wanted to avoid the Col d’Allos, where Beauvoir had once fallen into a ravine, and so decided to spend the next six days walking south through the mountains until I was back on the Mediterranean coast. I would pass through the village of Saint-Étienne-de-Tinée, where Beauvoir had once abandoned an exhausted friend who thought he could keep up with her on a nine-hour trek, and conclude my journey in the Côte d’Azur city of Menton, an area Beauvoir had explored one summer when she was staying in Nice to examine baccalaureate candidates.

Even in Beauvoir’s day the trails were mapped and bore markers, and she writes of her reliance on the Michelin and other guides she used to carefully map her routes. Today the trails are even more established. The region was named a national park, Mercantour, in 1979. Rustic dormitories with bunk beds and dinner were spaced a day’s hike from each other throughout the park, so I did not need to carry food or a tent. The most established trails had been systematized into thru-hikes that the French call Grande Randonée. My route would encompass parts of the GR5, which traverses the Alps on a north-south axis from the Netherlands to the Mediterranean, and one route of the Via Alpina, which traverses the Alps on an east-west axis all the way to Slovenia.

My intention was never to follow exactly in Beauvoir’s footsteps but rather to engage in the spirit of her adventures: to hike alone, to push myself, to improvise when necessary, but mostly to reduce my life to the simple goal of daily physical exhaustion. I had just finished writing a book and in recent months I had at times felt like my body had become a dispensable and burdensome object, that I could have just suspended my brain in a nutrient-rich amniotic fluid of Soylent and attached it to a keyboard, given how little I used my limbs. I wanted to exercise a discipline that made demands of my body rather than my cortex. Going on a hiking trip by myself in the Alps was also a way of testing the postures of Beauvoir, whose thinking about sexuality and gender had become increasingly influential to me. If the trip was miserable, then I would know, in a way, not to trust her.

It wasn’t only in her hiking trips that Beauvoir refused, as she put it, “to admit that life had any wills but my own.” She presented her life in her memoir as a set of principles rigorously adhered to: the commitment to sexual freedom in her relationship with Sartre, to independence from the domestic commitments of cohabitation and children, to happiness as a state that could be willed into being. Her obtuse optimism at times took on absurd casts: “It can’t happen to me; not a war, not to me,” she was still telling herself in 1939, as she walked through Provence.

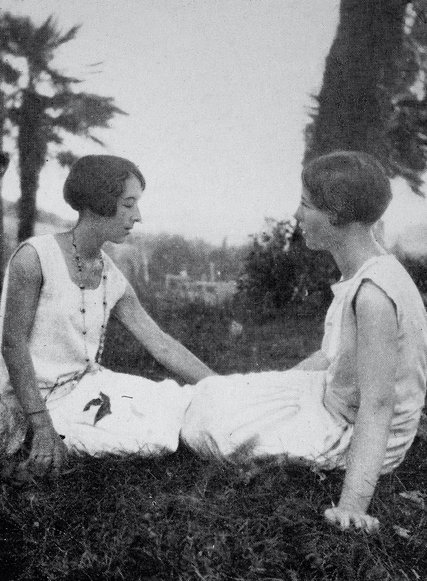

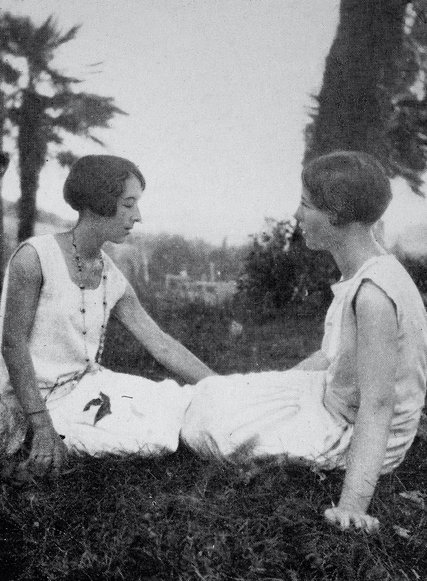

Beauvoir in 1945, four years before she wrote her feminist existentialist manifesto, “The Second Sex.” Credit Inner circle: Albert Harlingue/Rogerviollet/Getty Images; outer circle: Photo by Andia/Uig/Getty Images

I did not always believe either her ease of adjustment to the unconventional life she lived or the coherence she gave it in her memoir, which she published in 1960. I knew also that her refusal to let her ideas succumb to reality had led to her slowness to denounce Stalinism. But it was also her refusal to heed warnings and her rejection of self-pity that had helped her articulate feminism, to venture the then-preposterous question of whether anyone was really born a woman. Beauvoir believed there was a way out of the roles that society might try to impose on a person, by articulating a set of ideas about one’s life and refusing to accept evidence to the contrary. In this way, hiking was a disciplinary practice that applied to the other endeavors of her life. She set a goal, and once she was far enough in she had no choice but to continue. Nobody would rescue her and there was no possibility of evading the reality she had set out for herself.

I did not do my hiking in espadrilles and an old dress. I had hiking boots, nylon pants and a raincoat, a compass and maps. On two of the six days I walked with other people who happened to be traveling in the same direction, since I saw no reason to be alone all the time, but I was alone most of the time, and had full days of utter solitude. I met several men hiking alone, but no other women. In the evenings, at the hostels, my solitude was constantly remarked upon. I was told many times of my “courage,” which I translated from the French to mean foolishness. I would think of Beauvoir’s encounters with her colleagues on her solo excursions, of their “smiling disdainfully.” The weather was the same every day: sun and blue skies in the morning and a downpour in the afternoon. I hiked through meadows dotted with wildflowers and under stark gray peaks, through pine forests and streams. I saw marmots, chamois and a hoary ibex with a shaggy coat. I arrived in villages blooming with lilacs monitored by unblinking cats sitting in gardens, Saint Bernards and, once, a llama. I drank my coffee from a glass bowl in the mornings. I heard cowbells sounding through the rain like a Javanese gamelan and watched the mist rise out of fallen trees. I would lose the red and white trail markers, then suddenly spot them again. I scrambled across scree-filled passes whose rocks were purple in the rain and along patches of ice. I skipped a stage that would have had me hiking through ski resorts, accepting a ride in an empty school bus from a driver who took pity on me at the bus stop. Another day, in which I was grateful to have the company of a good-humored couple from Paris, we hiked 18 miles, sliding through mud down a hillside in a downpour and encountering a shepherd with the most extraordinary mustache I have ever seen, sheepdogs milling around him. I saw a lamb so small and new it still had its umbilical cord.

On the last day I had a daylong descent overlooking the Mediterranean, my knees on the verge of giving out as I picked through rocks and along switchbacks to sea level. The landscape had changed from a stark moonscape to humid deciduous brush to bleached rocks and semi-arid plants. Discarded jeans and plastic water bottles began to litter the underbrush, and then I was walking behind gated villas with manicured topiaries, swimming pools, an aviary of tropical birds. I emerged suddenly at a marina with a flat view of the sea. I had done it. I changed out of my hiking boots on a park bench as motorbikes whizzed along the promenade, then hobbled to the station to take a train to Nice. It was the first station after the border with Italy, and as I approached I saw a group of men of African and Middle Eastern descent being led into a police van, also carrying their backpacks.

It is a delusion to think that life has no wills but your own, or that you can thrive without the care and concern of others. But sometimes you can engineer a temporary condition, and produce a sense of accomplishment and self-reliance that uplifts you. For six days it was enough, as Beauvoir put it, to think of nothing but “flowers and beasts and stony tracks and wide horizons, the pleasurable sensation of possessing legs and lungs and a stomach.”

Correction: October 30, 2016

A picture caption last Sunday with an article about the feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir and her love of hiking reversed the identities of two women shown sitting in nature and misspelled the given name and misstated the surname of one of them. Simone de Beauvoir is at the right; the woman at the left is Élisabeth Lacoin, not Elizabeth Mabille. The caption also overstated what is known about the relationship between the two women. They were close friends, but it has never been confirmed that they were lovers.

Source: The New York Times

October 13, 2016

By Emily Witt

www.nytimes.com/2016/10/13/t-magazine/entertainment/simone-de-beauvoir-hiking-alps.html