The case against 12-foot lanes in cities, in 3 charts.

At first glance, it makes sense that wider traffic lanes could be safer traffic lanes. Drivers are prone to bad decisions and sleepiness and text messages and fits of rage. Providing some buffer room seems a reasonable way to keep them from veering into anything else sharing the road.

But as Jeff Speck persuasively argued during our Future of Transportation series, the conventional engineering wisdom that favors 12-foot traffic lanes to 10-foot lanes is deadly wrong—especially for city streets. The problem largely comes down to speed: when drivers have more room, cars go faster; when cars go faster, collisions do more harm. The evidence cited by Speck on the safety hazards of wider lanes is powerful, though to date it remains pretty scarce.

That body of work just got a bit thicker, thanks to a new study by civil engineer Dewan Masud Karim (spotted by Chris McCahill at the State Smart Transportation Initiative). Evaluating dozens of intersections in Toronto and Tokyo, Karim linked lower crash rates to narrower lanes—those closer to 10- or 10.5-feet wide than to 12-feet. Sure enough, wider lanes meant speedier cars, and yet narrower lanes were perfectly capable of moving high volumes of traffic.

He concludes:

Given the empirical evidence that favours ‘narrower is safer’, the ‘wider is safer’ approach based on intuition should be discarded once and for all. Narrower lane width, combined with other livable streets elements in urban areas, result in less aggressive driving and the ability to slow or stop a vehicle over shorter distances to avoid a collision.

Let’s take a closer, chart-filled look at the details.

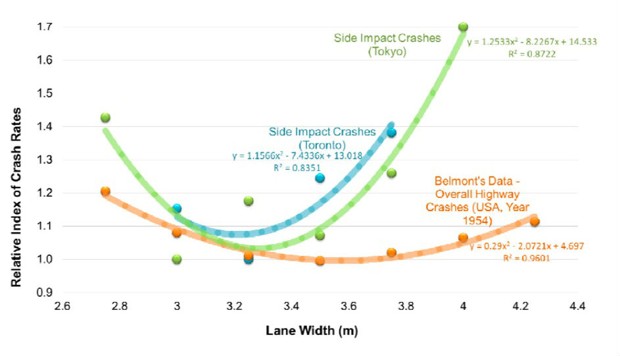

Narrow lanes are safer

An analysis of several years of crash data in both cities showed a clear sweet spot for lane width around 10.2 feet in Tokyo (3.1 meters) and 10.5 feet in Toronto (3.2 meters). Crash rates increased as lanes got too slim and drivers ran out of space; they also rose as lanes got wider. Karim writes that these results “clearly demonstrate why ‘conventional wisdom of lane width’ does not hold up to scientific scrutiny.”

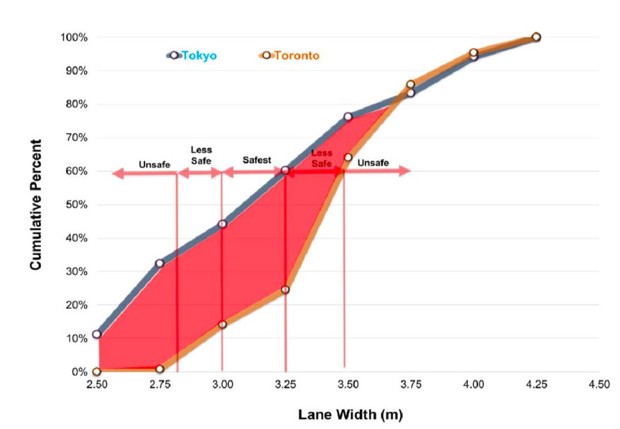

Cars in wider lanes tend to go faster

Generally speaking, traffic lanes in Tokyo are narrower than those in Toronto, with a much greater percentage falling into what Karim calls the “safest” width range. He believes wider lanes, and the faster traffic that comes with them, explains why Tokyo’s collision rates were lower than those in Toronto, despite the fact that Tokyo is a much more populous city with a greater traffic volume. At the time of a collision, the average speed of a car in Toronto was 34 percent higher than it was in Tokyo, according to Karim’s figures.

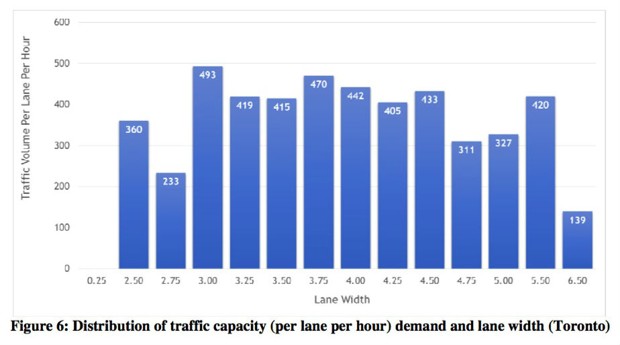

Narrow lanes still carry lots of traffic

A common rebuttal to reducing lanes from 12 to 10 feet is that doing so will produce congestion. But smart design can accommodate slim lanes and traffic alike—something New York City recently discovered when it narrowed car lanes to make way for bike lanes. Karim found that traffic capacity in Toronto was actually highest for lanes right around 10-feet wide.

“Traffic delays on urban roads are principally determined by junctions, not by midblock free flow speeds,” he writes. “Reducing lane width to 3.0 m [~10 feet] in urban environments should therefore, not lead to congestion.”

Source: The Atlantic CityLab

July 28, 2015

By Eric Jaffe

http://www.citylab.com/cityfixer/2015/07/10-foot-traffic-lanes-are-saferand-still-move-plenty-of-cars/399761/